Don't Give Up

The Diagnosis

Tamara does not usually ask me to go with her to the doctors office. But in spring 2000 a strange numbness in her legs and torso made its unwelcome return after a three year hiatus. My wife asked me to come along for her post-MRI screening.

Tamara also had an MRI in 1992. The possibility of multiple sclerosis had been a concern then, and we were relieved that the scan was negative. But the mystery remained unsolved for seven years. The doctor greeted us cordially before attaching Tamara’s MRI to the light fixture. And casually, he said “I’ve had a chance to look at your MRI, and it looks like you have a little MS here.” A wave of shock roiled over me as I scanned the image of her spinal column. A LITTLE MS? A LITTLE? But the earlier tests were negative.

“MRI’s pick up MS about 90% of the time, but it can be hard to diagnose in the early stages,” the doctor informed us as he pointed out the lesions where the myelin sheath around the spinal cord had been eaten away by her own immune cells.

“It’s not like it’s a death sentence,” the doctor tried to reassure us. Blood rushed out my head, and I quickly sat down on the bench. Last time I fainted in the doctors’ office, I ended up going for a very expensive ambulance ride to the hospital followed by an MRI of my own. Not this time! My job as husband and coach was to support her. I took a few deep breaths but remained seated through the rest of the consultation. Tamara remained composed and analytical.

An Ability to Focus

Focusing has always been one of her strong points. Just a few days before our doctor’s visit, Damien Koch, her college track and cross country coach at Colorado State University remarked to me that he always was so impressed with her ability to get the job done. “Boyfriends, classes, art projects, exams. She always had so much going on, and I could never tell what was going on in her head. But I always knew that Tammy would get in that 10 mile run. No matter what.”

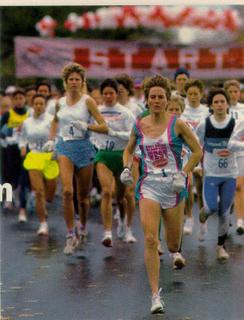

A 1980 graduate of the now infamous Columbine High School in Littleton, Colorado, Tamara played volleyball, basketball, and ran track. “In track I did everything but the high jump and shotput,” she says likes to tell friends. Tamara was not recruited out of high school, and enrolled at Colorado State to study art and graphic design. During the fall of her freshman year a coach encouraged her to tryout for the track team after he saw her running the school’s antiquated cinder track.

Colorado State had some talented women’s teams back in the 1980s. Tamara ended up as solid runner on a team that boasted several All Americans, including Libbie Hickman now America’s best female distance runner. By her senior year she had earned a full ride scholarship and All Conference honors at 1500 meters. Prodigious running aside, Tamara is perhaps best remembered for adding a little levity on road trips. When the team traveled by van to Arizona for a big spring invitational she once packed a couple of hand puppets. The dreaded “Wolf Cookie” mad opportunistic forays at snack time and pillaged with impunity. The puppets were there when the team arrived at the meet, but her track shoes were in Colorado. Almost 20 years later Koch recalls, “She has big feet. I had a heck of a time finding a pair of spikes in time for her race! But with those borrowed shoes she placed in the 800 meters, and had a great race.”

When the team went to Oregon for a fall cross country trip, they traveled to the coast beaches after the meet. While the other girls were sunning and relaxing, Tamara sprinted along the shoreline in her bikini screaming “I LOVE to run! I LOVE to run! I LOVE to run!”

Her college career ended with illness, injury, and burnout and she did not even make the traveling team for her final conference track championships. During the final weeks of the season, she asked me to join her a last ditch workout to get her back into race shape. Although we had been running together for almost a year, this was our first real workout. It could have been the last. She became irritable when we did not hit the times exactly on the first couple of repetitions. I pointed out to her that she needed to relax a little and make running fun. Although I half expected her to tell me to get lost, she listened. Then she asked me to coach her after the season was over.

The Graduate

Tamara graduated in 1985 with a degree in Graphic Design. And over the years she has made her mark by illustrating scientific manuals, college textbooks, and children’s field guides. A born artist, who has been drawing since she was three years old, she is regarded by clients for her ability to capture life on paper. A natural. Humans are natural endurance runners. Some are more natural than others. Tamara frequently lamented that her slightly built teammates in college were more efficient than her, with 5' 11" frame. However, Tamara is built to run. Unlike most distance runners, she runs on her toes. Her long legs glide over the ground without wasted vertical or horizontal motion. Narrow shoulders and thin arms make her stride all the more efficient. In college she developed good habits in technique and worked assiduously to maintain her form. Her only idiosyncracy is the slight hitch in her arm carriage, when her right forearm wanders across the plane of her mid-section. After taking a much needed post-college break Tamara moved up from the middle distances and improved steadily at everything from 5k to the half marathon.

But a plethora of world class runners live and train in Colorado, and Tamara was frequently overshadowed by stars from the U.S. and places like Norway or New Zealand. In 1989 we moved from altitude to Ithaca, New York where she went on a spree of setting course records and top finishes at big races. The bigger the race, the tougher the competition and conditions, the better she would perform. During the summer of 1989 we decided to focus on the track, with the Empire State Games as the peak race.

The Empire Games are the oldest and largest of state games in the USA. However, not everybody gets to go to the Games. About five or six weeks before the Games, runners must qualify in an Olympic Trials like track meet. Only 12 in the whole state make it. The Central Region coach was awed when Tamara “came in from nowhere and blew away the competition by 40 seconds” in the 5,000 meters qualifier. After a series of excellent races and workouts, her performances had garnered considerable attention among the local running community. However, the Games arrived with stifling humidity and broiler heat that radiated off the astroturf infield, asphalt track, and cement stadium at Cornell University’s track venue.

The 5k is probably the most popular distance for road races. Joe or Jill six pack runner can easily manage a 5k, even if they only run once or twice a week. But there is nothing easy about racing the 5k or 5,000 meters. The race IS the measure of your maximum aerobic capacity, otherwise known as the V02 max. To find your aerobic capacity and run a fast 5k is to ask your body to hurt. There may be a million ways to run the distance of 5,000 meters, but no matter how you do it, you will have to endure an extended bout of oxygen deprivation and burning legs. As Frank Shorter says in opening segment of the Steve Prefontaine movie, Without Limits, “this race is about pain.” A savvy runner can use this pain to their advantage. A good rule of thumb is to hit your opponents at their weak points--when they let up. That was our plan for the Empire Games.

Tamara was to follow for the first four or five laps at about 82 seconds per circuit, and when her competitors began to ease off a little, drop the pace to 80. The leaders took off quickly on the first lap, and Tamara spotted them about 10 meters. The pack coalesced and settled into an even pace, averaging 82 seconds per 400 meters. Just as we expected, the pace slowed on the fifth lap and Tamara took the lead, and charged through consecutive laps of 78 and 79 seconds. The lead pack disintegrated. The gold was never in doubt as Tamara increased her lead by about second with each loop around the hot black oval. She ran a 17:08 to win by 12 seconds. We were hoping for a sub 17, but were not disappointed because she had raced to win. Tamara had executed the race perfectly, and ran with guts under less than ideal conditions.

Her confidence buoyed with that win, and over the next year she went on a racing rampage. Two weeks later she placed in the top 20 at the U.S.A. 10k road racing championships in New Jersey. After a late summer break, she returned to form on a cold, wet, and blustery day to take third at the Northeast Regional 10k Road Championships with a PR of 35:01. The winner, a reserved New Englander, by the name of Lynn Jennings, told the press after the race “today was not a day to run for fast times.”

At the end of the 1989 season, we traveled from the hinterlands New York’s Finger Lakes to Rhode Island for the prestigious New England Cross Country Championships. On the soul of her left shoe Tamara painted a butterfly, on the right a bee. Like Muhammed Ali, she vowed to “float like a butterfly and sting like a bee.” Over a gnarly 5k course at Bryant College, Tamara floated over the roots and large cobbles and stung a bevy of Chowdaheads to take an impressive third place. First place that day went to Gwyn Hardesty (nee Coogan), who would make the 1992 Olympic team. Second was Karen Smyers, who became the U.S.A’s top ranked triathlete a few years later. That day we heard a lot of “who’s that blond girl?”

Over the next spring and summer it seemed as if every race was a PR or a breakthrough. I couldn’t even remember the last time she had run a “bad” race. She ran a PR 16:58 at Friehoffers, good for 13th at the U.S. road 5k championships. Friehoffers is not known for it’s fast times. Said eight time champion Lynn Jennings after winning in 1998, “The race is held on a course that requires a strategic and intelligent race execution.” Tamara took top five at a string major road races, which included The Lilac 10k, Utica Boilermaker, and Buffalo Subaru 4 Mile Chase. At Utica she was the top New Yorker. Although the sub 17:00 5k, eluded her, in July she ran a PR 22:05 at the Buffalo Subaru 4-Mile. Her reputation was growing, and it seemed that it would be just a matter of time and the right conditions before she would nail a 5k in the 16:40's or faster.

To Defend the Gold

She would defend her 5,000 meter gold medal at The Empire Games during the last week of July. This time the race on a rubberized all weather track in Syracuse. The heat and humidity were absent. I felt that this would be her day. As we drove to the race, Tamara commented that she was not “into the Empire Games this year,” that the event was “kind of high schoolish.” I was a little surprised when she said “I want to take a year or so off from running and racing.” I figured that these were just those pre-race negative jitters that plague us all before a big competition.

The race plan was much the same as for the previous year. Let the others do the leading for the first mile or so, drop into 80 second per lap pace, and leave the field behind. After her performance at Buffalo, I did not think she would have any problem with the pace or any runners in the field. The first four or five laps went exactly as planned, and she took the lead with an 80 second lap. The pack broke up, and the race was shaping up just like the last year. But this time, she had a shadow. Lori Hewig from Albany tucked closely behind Tamara. I recognized Hewig from Friehoffer’s that spring, but Tamara had beaten her there. Tamara knew how cope the contingencies after the breakaway: if someone sticks with her, then surge another lap; if they’re still there, drop back and let them lead until 1,000 meters to go, and then put the hammer down for a long drive to the finish. Tamara did not surge, and dropped back into 82's and 83's for the next few laps. Lori stuck close behind. She was about the same age as Tamara and obviously quite talented, but less experienced. Tamara tried to shake her. “It was driving me nuts,” she has recounted many times since that day in the summer of 1990, “I tried to pick up the pace, but my legs just wouldn’t go any faster.”

By 3000 meters I became concerned, and yelled for Tamara to either pick up the pace or let Lori lead. Tamara slowed to 83's and 84's but did not exchange the lead over the next three laps, and I grew a little annoyed when she did not seem to be sticking with the plan. Her race face, normally placid and in deep focus, took on a frown of frustration as she headed down the homestretch with two laps to go. Finally, Tamara stutter-stepped into a near jog as if to let Lori know that the heel clips were no longer welcome. Lori hesitated momentarily, and then her coach yelled for her to go, and she took off with a strong kick. Tamara did not pursue, but held on for the silver in 17:21.

“I Need a Break”

I had never seen Tamara give up in a race. It seemed uncharacteristic for her to let Lori go without a good fight. On the way home we agreed that she needed to take a break. She decided to rest through most of August, train for a low-key fall cross country season, and then take a whole year off from competition. After a rest, she maintained her training at 40 miles a week, about eight or ten miles less than she had been used to. Although she won the Upstate New York Cross Country Series with ease, she was not the same. Within two months of the best races of her career, I noticed that her knee lift and turnover were lagging ever so slightly. We stayed away from the roads and did exercises to get the spring back into her stride. That fall and winter, the first of a series of strange symptoms began to appear. It started with an inexplicable irritable colon. A few months later she experienced a strange numbness and tingling in her feet, and legs. Sometimes the muscles around her eyes would twitch. She saw several medical specialists, but none were able to offer a diagnosis.

Cycle of Mystery

True to her promise, Tamara did not race during most of 1991. She returned only to run fall cross country. She defended her Upstate New York series title, but her stride did not improve even though we had worked on the knee lift and turnover.

By 1992 we had moved to the outback of North Dakota, and Tamara said she was ready to return to racing. After an easy buildup and some small races she lined up for a 3 mile race in Dickinson, ND against Becki Wells, who was the top high school distance runner in the country. “I had read about her and wanted to give her a challenge,” said Tamara. And challenge she did. They ran stride for stride for more than two and a half miles, but on the final hill Tamara recalls, “my legs just shut down.” She had to walk to the finish. A few weeks later, on a hot 14 mile run, she had to stop and walk after 11 miles. The next month the numbness returned with a vengeance. But rather than just tingling, her legs were hobbled. She could not run and barely could walk around the block. A series of tests to detect a cause, from tumors or pinched nerves to Lyme Disease or MS, all showed up negative. We and the doctors were baffled.

Over the next seven years--which included the arrival of two healthy boys in 1995 and 1997--the pattern continued. She would build up her base, and be on the cusp of good racing shape; then the symptoms would return, and she would have start over again. More visits to the doctors, and it seemed each had a different hypothesis. By the late 1990s we thought that the mysterious problem had passed. She had not had any symptoms in over three years, an had been working out regularly with running, weight lifting, swimming, and volleyball.

On May Day in 2000 she entered the 2 mile “Furry Scurry” a popular human-canine fun run in Denver. Tamara and Roxie, a border collie mix, glided through the course in under 13 minutes and made a top 10 overall finish look easy. I figured that with a buildup to 30 miles a week and some consistent speed work, she’d soon be able to run a 5k in under 20 minutes. A comeback was just around the corner. A week later the numbness returned to her legs, followed by a strange burning sensation on her torso. Was it stress? Overdoing the running, weightlifting, and volleyball. A pinched nerve in her spine? More doctors. More tests. Then the diagnosis: Tamara has recurring-remitting multiple sclerosis.

About MS

Multiple sclerosis is an autoimmune disease that afflicts approximately 350,000 Americans. So far there is no definitive cause, although viruses are suspect. MS has no cure. What is known is that the body’s own immune cells work overtime and attack the myelin–the protective sheath that surrounds the spinal cord. Myelin is like the plastic coating on electric wire, and without it nerve conduction slows down. Multiple sclerosis is not passed on genetically, although there appears to be a small but significant familial predisposition. The disease affects women about twice as often as men. It is most common in mid or higher latitudes and among Caucasians. High altitude regions like Colorado often have the most frequent number of cases.

MS is not always a progressive degenerative disease. Many people may have a bout, and never know it. Some may have the recurring-remitting type for decades, but will live well into old age. Sometimes these attacks become more frequent and progressive. The course of the disease is very unpredictable. Just a generation ago MS patients, like Olympic skiing medalist Jimmy Huega, were told to stop their athletic activities. But pioneers like Huega fought the medical conventional wisdom, and continued to exercise. Now physicians recommend that MS patients should continue with a moderate exercise regime. In spite of all of the gaps in our knowledge about MS, many of the symptoms can be managed. Recent medical advances have brightened the outlook considerably. There are now medications available that can alleviate the symptoms, and reduce the frequency of attacks. Cutting edge medical research has shown that myelin in mice can be regenerated from embryonic tissue. Unfortunately the current political climate in the U.S. against any and all stem cell research. In half a generation we have gone from the dark to the potential ability to restore damaged neural tissue.

Coping

Although possible breakthroughs appear to be promising, it is impossible to predict the future. We appear to be a long way from even pinpointing the cause of MS, and without that knowledge there is no cure. The disease itself is unpredictable; no two cases are the same. Tamara and her doctors do not know for sure if the current stiffness in her knee will go away, and no one knows when another attack of numbness will return or how long will it last. Our life and our outlook has changed forever. Now we know that a comeback is not likely. “It’s like being permanently injured,” says Tamara.

I think of the Peter Gabriel-Kate Bush duet “Don’t Give Up.”

don’t give up ‘cause you have friends don’t give up you’re not beaten yet don’t give up I know you can make it good

Instead of planning and executing regular interval workouts, we now count the duration between recurring attacks. The nagging wonder whether some elite opponents at major races were taking performance enhancing drugs has been replaced by the knowledge that Tamara will need to take steroids from time to time. These are powerful drugs that affect her mood and ability to function through a busy day. However, we are grateful for their availability. My role as a coach 10 years ago was to encourage her to push through pain barriers in the tough middle and late stages of a 5,000 meter race. Now at the end of the day I provide the support she needs to make an injection with Copaxone, a drug that reduces the frequency of attacks.

Tamara no longer writes things like “Sting Like a Bee,” on her shoes. But for an hour or two after the injection, she says that it feels just like a bee sting. As her coach, my biggest challenge was hold her back from pushing too hard. On a recovery day I would say an easy six or eight miles would be fine. But when I returned home she would say that she ran 85 minutes, “But it was such a pretty day.” I would just role my eyes and say “You’d better cool it, Girlie.” Now we know that moderation is imperative. Long or exhausting workouts, especially in the heat, can exacerbate the symptoms. Much of coaching is psychological. Most anyone can look at book and write up a 10 week training program. A coach has to think about the long term. Coaches must convince their athletes that barriers can be broken. That anything is possible. The biggest challenge for most runners is to face the fear of the unknown, and to fight those mental barriers. To cope with MS is to face the fear of the unknown. We do not know what will happen the course of Tamara’s disease over the next five, ten, or twenty years. We do not know what advances will be made by medicine during the next few decades.

To ask why is natural. But better than to ask “Why me? Why us?” we need to wonder why do autoimmune diseases occur in the first place? Why is MS so prevalent in high elevation locales like Colorado? Why do four of Tamara’s teammates from Colorado State University--All Conference or All Americans from the 1982-84 era--have serious autoimmune disorders like MS, lupus, or fybromalagia?

don’t give up cause you have friends don’t give up you’re not the only one don’t give up no reason to be ashamed don’t give up you still have us don’t give up now we’re proud of who you are don’t give up you know it’s never been easy don’t give up ‘cause I believe there’s a place there’s a place where we belong

We have many reasons to be thankful. After a decade of a nomadism we had returned to or home of Colorado, close to friends and family. A place where we belong. We have two lively boys who keep us running from dawn to dusk. At times we wonder if it is not such a good idea for a couple of distance runners to have children. Our kids go non stop. But they add sunshine to our lives. All the uncertainty and questions notwithstanding, we have a goal: When our children graduate from high school and college during the next 15 or 20 years, we will include a run together as part of the celebration. The boys will be welcome to join us.

Postscript 2005

This story was written in 2000, a year after Tamara’s diagnosis. The good news is that she continues to take medication, and her heath remains stable. She has moderated her activity level but still enjoys going out for an occasional run or ski. We no longer live in Colorado because we felt that the summer weather was too hot for her condition and because the Front Range was becoming overgrown. In 2004 we moved to Alaska, which is neither hot nor overdeveloped. Tamara is coaching elementary school runners and volunteers at races.